Accidental Genius: Traumatic Brain Injury Changes Perception of Mathematical Art

By Ahana Mandal

There are some in the world with unbelievable talents — accomplished soloists by their early teens, math geniuses accepted into MIT — who seem to be gifted with their abilities since birth.

But what if those abilities were acquired later in life — by accident?

That is the true story of Jason Padgett, an artist specializing in interpreting math through pixels and selling his works through his business “Pixels”. He acquired savant syndrome of mathematical synesthesia from a head injury following a fall at a karaoke bar. In his childhood, he didn’t care for school - other than lunch or recess, he had zero interest in school subjects, especially math. He actually had to repeat his high school senior year because he had skipped so much school — an anomaly among the selective group of individuals with these unique talents. His carefree attitude about school didn’t stop at college either; in his Ted Talk, he recalls that “as long as we could party, chase girls and goof off,” he was living a good life. Or that’s what it seemed to him then — but he says that his life was “a mile long, but only an inch deep.”

Life continued in the same manner for him for an additional decade, until a fateful night in 2002. He headed to the karaoke bar with some friends and offered them a ride since they were too drunk. However, as they left, there were two thugs who had paid off a server to tell them who had cash walking out and robbing the customers. In Padgett’s case, it turned quite violent. He “was attacked from behind from my perspective; I didn't see anything at all. I just heard and felt this deep thud in the back as something smashed into the back of my head, and I saw this flash of light similar to what you hear boxers describe when they get knocked out.” At that moment, he thought that his life would end right there, but he ended up trying to defend himself by biting one of the robbers, but he ended up cracking his teeth. Eventually, the robbers made it off with his jacket, but Padgett ended up going to the hospital for his injuries. He was diagnosed with a concussion and a bruised kidney and sent home with a powerful narcotic shot for his extreme pain. He noticed that he was seeing things weirdly, but he dismissed his skewed vision as an effect of the drug.

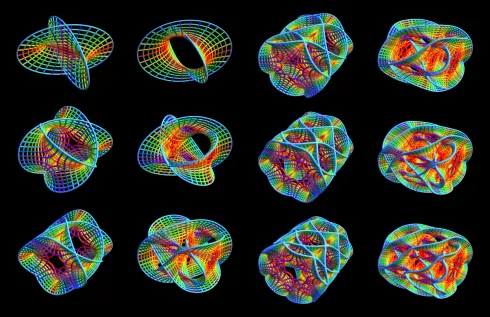

But when he woke up the next morning, he realized that it was, in fact, not the narcotic that had caused his vision to change dramatically. He recalls that “when things moved, they moved in these bizarre stop action frames like individual discrete picture frames with a line connecting them and bright light seemed somehow amplified, and the jagged edges of these picture frames made these beautiful and elegant patterns as things moved.” He describes his initial reaction as being of awe, being mesmerized by what he began to realize how our brains construct moving images for our brains, and then puts it all into a continuous timeline and smooths all the images for us to understand what is happening in front of our eyes. Everything he saw, even his hands, looked utterly new because everything that appeared to him lost its smoothness or continuity - everything had straight, discrete lines.

He did question himself if he would ever tell anyone about his newfound way of vision, and once he did, he described it as watching the television but watching all the scenes frame by frame. That is how he sees life happening in real time.

However, he didn’t really get into involving himself in the mathematics field until his daughter Megan brought up a simple yet intriguing question - if the television showed images because every small, rectangle pixel on the screen changed color, then how could circles form. And what Padgett realized is that perfect circles will never exist; even if you zoom in and zoom in and keep zooming in, the “smooth” edges of the circle will always be the jagged edges of very, very tiny rectangles.

His newfound synesthesia didn’t come easy, however; he developed OCD, agoraphobia - the fear of leaving the house - and post-traumatic stress. He locked himself away in his home for three years until he drove to the mall because there was zero food left in the house. At the mall, he met a physicist, and when the two began talking, he began to realize that the two of them were talking about two similar things, but ultimately completely different.. While the physicist talked about the function and the big squeeze theorem of pi, Padgett saw the visual representation of pi in front of him and saw that pi would get smoother as there were smaller and smaller pixels, forever approaching the shape of a perfect circle but never achieving it. They continued to talk about exponents and even fusion, and Padgett continued to explain things with visual representations - a very unique reasoning for the mathematical principles that are foundational in the fields of science and math. That same physicist encouraged Padgett to return to school to learn traditional mathematics so that all of them would be able to understand what he was saying in a common language.

As Padgett says, “he gave me the best advice of my life that day.” He enrolled in an Algebra 99 class, where his professor, Tracy Haney, first grafted an equation, and when he realized that he was indeed grafting equations in his brain, he became hooked on this newfound knowledge. Cooped up in the math labs, he was hungry for the knowledge of the world that he hadn’t taken a glance at before and was knocked to the core when his friend came by with pictures of interference patterns of ordinary projects that were very similar to the images he saw in his head. This gave him the confidence that he wasn’t the “crazy guy who thought he saw math everywhere but really didn't and so it gave me this feeling that yes I was on the right track.”

He then finally found his life purpose; when he began talking to a woman — who would then become his wife and have a daughter with him — he realized that when explaining these complicated math concepts with images of what he saw and using common phrases easy to understand, it was a far more comprehensible way of teaching mathematics for students to absorb and retain. He wanted to inspire future scientists, and he would do it through his strange but helpful ability to see all sorts of concepts and equations through discrete patterns.

A whole life, once only an inch deep but now filled with a fulfilling purpose, thanks to a fight at a karaoke bar and math.